The Village and the Country

Even in this little corner of the Salish Sea, we're not immune to the forces operating elsewhere on the West Coast: astronomical land prices, rapidly expanding population, and deepening cultural divides. Some celebrate "progress," some decry "gentrification." For many years I thought that Lopez was different, that our that our live-and-let-live culture would enable us to get along, and despite regular spasms of tribalistic infighting, we were truly a "capital C" Community.

Now I'm not so sure. Setting aside the traditional red/blue political differences, I'm seeing an increased splintering of values & priorities even within the liberal/leftist/progressive-identifying folk. This is also happening in America at large, so it shouldn't surprise me—but it's harder to see it here, in my home.

Here's my late-night impetuous and utterly unverified theory of why Lopez' blue/lefty types are starting to get on each other's nerves more often: we're experiencing the urbanization of a once strictly rural community.

See, the lesson the hippies who dropped out and ran to the woods learned early was this: the rednecks are good folks to know, and emulate. The old-timers taught the hippies how to take care of themselves and be useful: how to grow a garden, can vegetables, raise chickens, build a chicken coop that the raccoons and minks can't get into, keep an old tractor running, shoot and dress a deer, knit socks. The old-timers taught the suburban refugees how to drop in for a visit, how to put on a barn dance, how to stop in the middle of the road to exchange news. They also passed on some traditional rural values that might be called "conservative": be self-sufficient; don't depend on institutions; be skeptical of grand schemes; spend the winter.

I came early enough that I got to know a few of these old country folks before they passed on, and to learn from those who learned from the old-timers. Many folks still keep this traditional knowledge alive, and are passing it on to younger folks, to the kids who grew up here and returned, to the newcomers who have discovered the hard but rewarding life there is to be found here.

Meanwhile, over the past twenty years a lot of homes have been built in the Village, and more businesses have cropped up there. We just got a fancy new farm-to-table restaurant that was touted in the Seattle Times. Not to pick on these guys—I hear the food is amazing—but their website describes the restaurant's "idyllic island setting."

"Idyllic" describes an idealized, peaceful & picturesque scene, usually a rural one. Anyone who actually lives in a rural area understands that "idyllic" isn't reality, it's marketing. Very few of the farmers here could afford their land without an inheritance or other outside help. Some farmers had successful corporate careers before landing here.

This is all wonderful in its way; this influx of outside money has enabled the development of a robust rural food production network, which in turn has attracted ancillary enterprises like new restaurants. But this flood of money from Seattle and 401Ks has also made us more vulnerable; our economy is more than ever dependent on tourism, and if we remember the Great Recession, tourism can be a fickle foundation upon which to build a resilient life.

And so, too, we are losing that scruffy independence that characterized Lopez of the 70s thru the late 90s. No one can move here now and build a simple off-grid cabin, and so the basis for an independent life—a mortgage-free homestead—is no longer an option. Ya gotta have money now, and that will limit the options and creativity of folks who might want to come here and get a taste of this particular way of life.

I'm increasingly getting the feeling that I'm living in a sort of Colonial Williamsburg featuring West Coast hippies. The "island lifestyle" is trendy and cool, the landscape filled with Instagram-worthy farms. The locals are merely a backdrop to people's vacations, anonymously flower-crowned and thrift-shop shod. Just another tourist town, primed for consumption.

Those of us who have been here a while can see the decline of the Country, and the rise of the Village. What can be done, if anything? Should we lament the passing of this funky old Lopez life, or let it pass away unmourned? Is this a culture worth saving?

Village |

Country |

|---|---|

| Eating out |

Potluck |

| Coffee shop |

Road conference |

| Tree lighting |

Maypole dance |

| Smartphones | Guns |

| Prius | Pickup |

| Wine tasting |

Brewfest |

| Costco | Canning |

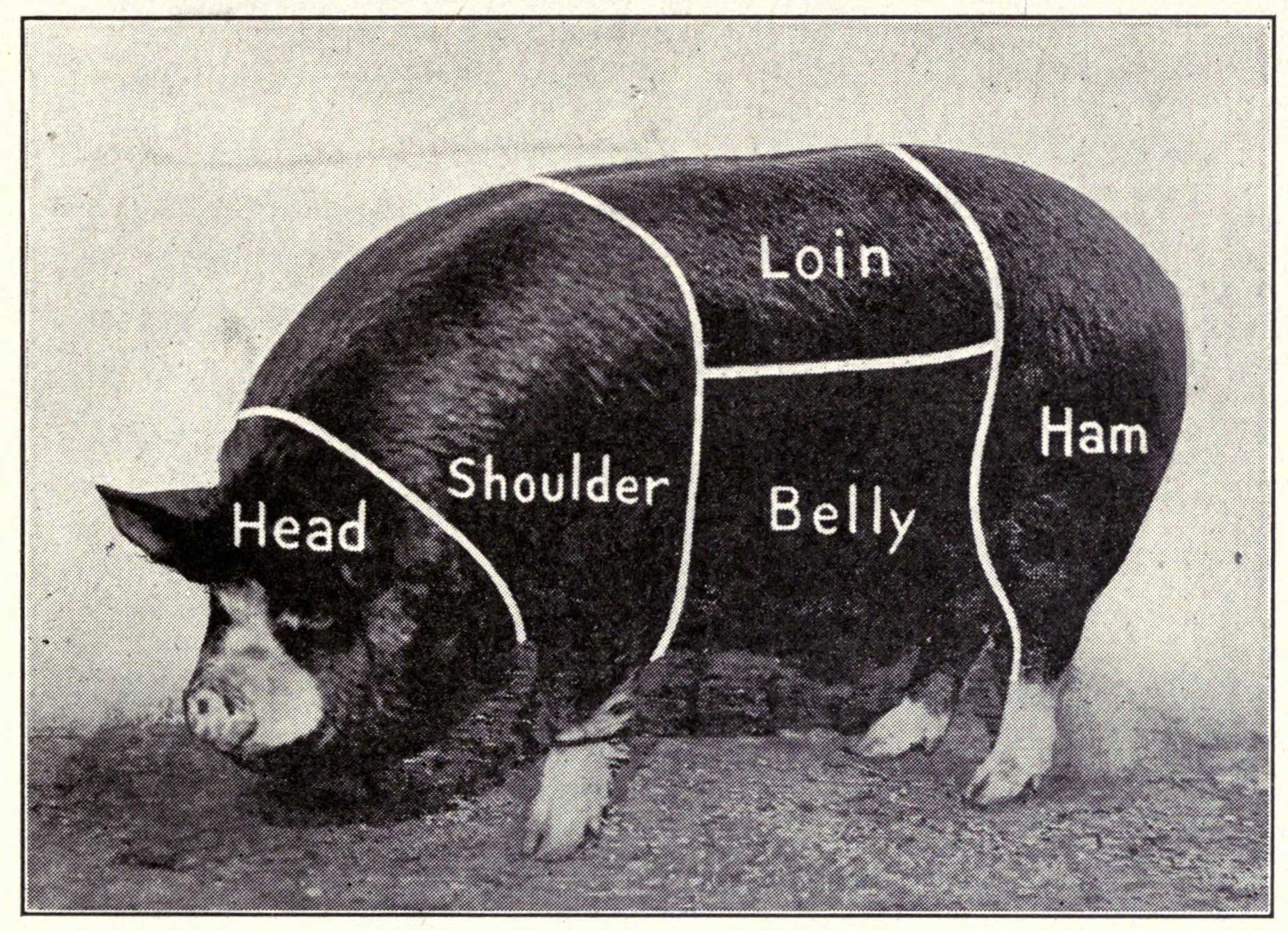

P.S. If you can keep pigs, you're in the Country.